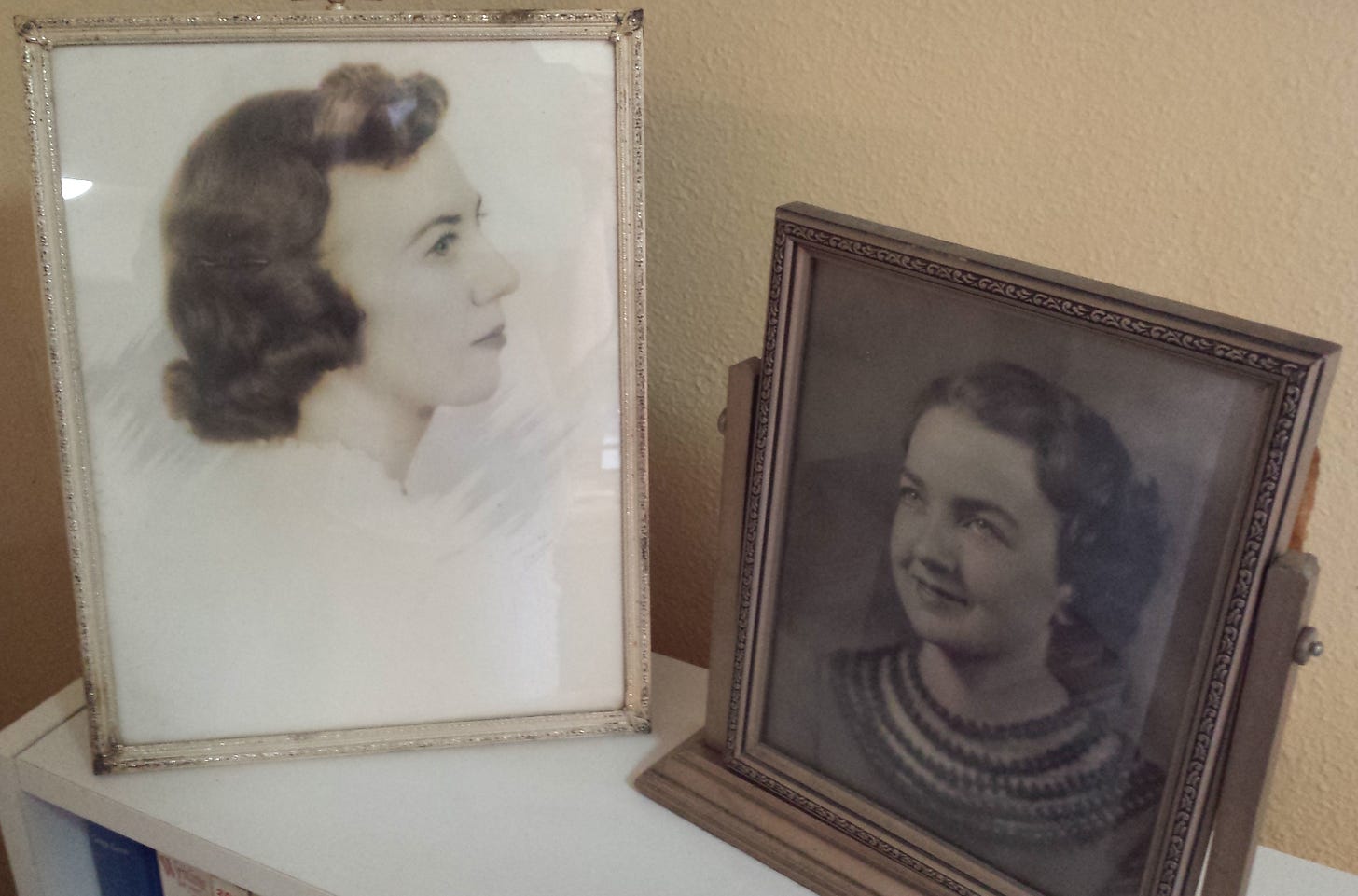

Happy Mother’s Day! In honor of this day and all the women who have shaped us, trained us, carried us, cooked for us, bandaged us, badgered us, and taught us to remember who we are, I’d like to share an excerpt of an essay I wrote about my mom, Clara May Landwehr. Called “Oral History,” it originally appeared in the book My Mother’s Garden: A Collection About Love, Flowers, and Family.

My mom died in 2005, at the age of 90. I wrote this not long before she passed.

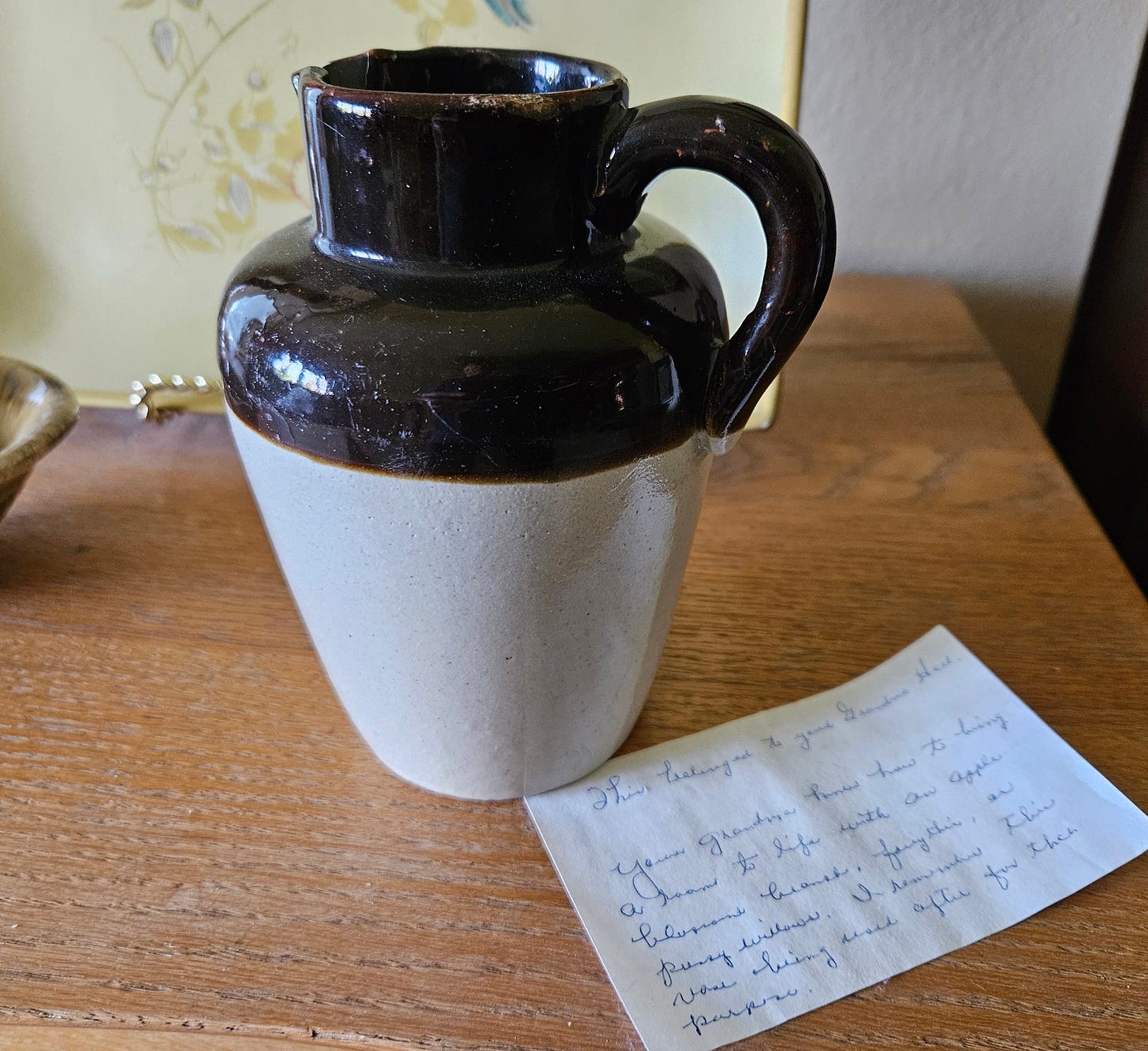

When I turned forty-eight, my mom gave me a stoneware pitcher that she remembers from her childhood. Inside it, she tucked a handwritten note that says, “This belonged to your Grandma Hall. Your grandma knew how to bring a room to life with an apple blossom branch, forsythia or pussy willows. I remember this vase being used often for this purpose.” I brought home the vase and filled it with two branches cut from our burning bushes. They lit up the kitchen table for several days before the crimson leaves started to fall.

My grandmother was magic with roses, my mom says. She could take a cutting from a rose, put it in water, turn a fruit jar over it and set it in the sun, and it would grow. “I’ve tried it two or three times and never had any luck,” my mom says.

Like her grandparents, my mom’s parents gardened not just for beauty, but to live. A garden was sustenance, insurance that no one would starve through the winter.

My mom remembers watching Bernie, the hired hand, walking behind a mule and a plow as her father cleared fields of trees, and how the plow would get hung up on the tree roots, and Bernie and the mule would keep going. She remembers how rich that soil was, a storehouse of energy from hundreds of years of decayed leaves. She remembers how she and her sister Grada made hats out of saucer-sized sycamore leaves, pinning them together with thorns. She remembers that, while her father cleared land, she built miniature cemeteries, using rocks for tombstones and gathering flowers to lay on the pretend graves. This, she says, might have been a tribute to her twin brother, who died when they were almost three.

She remembers walking to Myrtle once to buy a quarter’s worth of sugar, which she estimates now at about two and a half pounds. She had to cross the creek on a swinging bridge, which was fun one minute and scary the next. Her mother bought coffee and peanut butter. And she bought flour to make the breakfast biscuits she served with fried squirrel. She made dumplings, too, and quail pie. My mom says, “It was the best thing I ever ate.”

My mom’s memories of her mother and grandmother are connected, because her experience of them was simultaneous. That’s why I’m surprised when she tells me she doesn’t know where her mother grew up. “Mama talked about what a beautiful spot it was,” she says. “It sounded like the Garden of Eden. I’d give anything to know where it was. I think it was over the line in Arkansas.”

Then she tells me a story about her cousins, relatives whose names I’ve heard but can’t picture in the family tree. It seems that a relative named Rufus signed a paper pledging not to get married until his father died. Rufus kept his word, taking care of his ailing father, and postponing his own marriage. When his father passed on, Rufus moved with his bride to the family farm, which he inherited in exchange for his commitment.

The real point of the story is that the bride had a son, a young man named George, who dated Grada for a time. When my mom, at the age of 18, took a job in Jefferson City, Missouri, she ran into George and started a relationship of her own. “That always pleased me,” she says, “because Grada stole some of my boyfriends.”

Ah. So my mom still has the spirit of a young girl. Maybe it’s because her mother was a branch of apple blossom, a cutting from a rose, a bit of lingering mystery.

A few years ago, for another birthday, my mom gave me the latest quilt she had finished. It’s a Flower Garden quilt, a design of small hexagons, some cut from prints, some from solid muslin. My mom started it as a teenager and finished it six children and six decades later. She edged it with a narrow red binding, a metaphor for the brick border around her flowerbeds.

Her flowers ringed our backyard, growing even in a bed south of the house where only our next-door neighbors could see them. Because of my mom, I lived my childhood in proximity to flowers. They were always in the background, even when my mom bundled them up and set them in a vase with their arms outstretched and their heads held high, and they filled the house with fragrance. I was not a gardener, my mom did not teach me to garden. But they were there, a backdrop of tulips and poppies for my childhood.

My mom did not intrude. She did not give advice. She did not teach me to shave my legs or talk to boys or apply lipstick. She did teach me to sew and to make meringue cookies with chocolate chips and nuts and to stir cornbread into a glass of milk the way she had in the Ozarks as a child. But she did not teach me to love flowers. Like her mother and grandmother, she just loved them herself.

On my mom’s coffee table are computer printouts showing antique pump organs. Her cousin in Arkansas has the organ that my mom and Grada played when they were little. My mom hasn’t seen the instrument since about 1930; she didn’t know it was still in the family. One of the printed photographs reminds her of her grandmother’s organ, with Victorian scrollwork and shelves for bric-a-brac. My mom remembers playing this one, probably on those days when there was no way to cross the creek, and she and Grada lived with their grandparents, smelling the lilac bush by the front porch and admiring the field of daisies across the road.

My mom’s cousin doesn’t have room for the organ anymore and wonders if someone in our family would like to have it. Thinking about the organ has made my mom remember her grandmother’s garden. And recalling her grandmother’s garden has made me think about this thing called generation and legacy.

I am trying to sort out nostalgia from longing, as if there were any difference. I think of rocks that became headstones, and sycamore leaves that became hats, and berries eaten on the way to school, sometimes falling to the ground and squishing up between bare toes like the dust in the road. I’m thinking about a time when life decisions were dictated by a swollen creek, and you had everything you needed to survive growing within a few dozen yards of your house.

I am thinking about the ways we come to know one another. I will never hear the exact words of my great-grandmother or grandmother, although they speak through the generations in the language of flowers. But I can get a glimpse of them, and the glimpse becomes a picture, just as every river or apple tree or gooseberry bush is part of the earth and is the earth, all at the same time.

I have been taught that, if you turn your inner and outer world into a garden, people will come and sit with you there. I come often to sit with my mother. Today, I have learned something important. I have learned that my mother, like the women before her, is the scent of peaches drying on a roof, the energy of a rose sprouting in the sun, the perennial flowers that form borders and backgrounds in quilts and backyards.

From generation to generation, mothers and daughters pass a link to the earth. An omnipresence, always rotating, always giving life.

‘A WHOLE NEW WORLD” IS A READER-SUPPORTED PUBLICATION. To receive new posts and support my work, please consider becoming a paid subscriber at whatever level you’re comfortable.

A NOTE TO MY READERS: I write “A Whole New World” as a member of the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative, which is led by Julie Gammack, of Des Moines. I’m honored to be part of this group, featuring the diverse voices of more than 50 professional writers and journalists across the state of Iowa. I encourage you to check out their columns.

Here’s our line-up:

Nicole Baart: This Stays Here, Sioux Center

Ray Young Bear: From Red Earth Drive, Meskwaki Settlement

Laura Belin: Iowa Politics with Laura Belin, Windsor Heights

Tory Brecht: Brecht’s Beat, Quad Cities

Dartanyan L. Brown: My Integrated Live, Des Moines

Jane Burns: The Crossover, Des Moines

Dave Busiek: Dave Busiek on Media, Des Moines

Iowa Writers Collaborative: Roundup

Steph C: It Was Never a Dress, Johnston

Art Cullen: Art Cullen’s Notebook, Storm Lake

Suzanna de Baca: Dispatches from the Heartland, Huxley

Debra Engle: A Whole New World, Madison County

Randy Evans: Stray Thoughts, Des Moines via Bloomfield

Daniel P. Finney: Paragraph Stacker, Des Moines

Arnold Garson: Second Thoughts, Okoboji and Sioux Falls

Julie Gammack: Julie Gammack’s Iowa Potluck, Des Moines and Okoboji

Avery Gregurich: The Five and Dime, Marengo

Fern Kupfer and Joe Geha: Fern and Joe, Ames

Jody Gifford: Benign Inspiration, West Des Moines

Rob Gray's Area: Rob Gray’s Area, Ankeny

Nik Heftman: The Seven Times, Iowa

Beth Hoffman: In the Dirt, Lovilla

Iowa Capital Dispatch, an alliance with IWC

Iowa Podcasters Collaborative,

Iowa Podcasters' Collaborative

Oops. Thank you, Jim! Will you be my proofreader? :) Much appreciated.

This was a lovely tribute to your mom. I don’t mean to be pedantic, but the first line uses picture instead of pitcher.